Introduction

An important and reliable source of effective therapeutic leads that come from Earth's biodiverse flora and fauna are natural substances generally referred to as "secondary metabolites" (the end-products of gene expression).1 A wide range of biological sources, including both prokaryotic (eubacteria, 92 cyanobacteria), and eukaryotic species, have allowed for the identification of more than 30,000 chemicals of marine origin over the course of five decades of persistent investigation (fungi, dinoflagellates, algae, sponges, cnidarians, bryozoans, 93 mollusks, ascidians, and echinoderms).2, 3 The Earth's oceans, which cover over 70% of the planet's surface, present an extensive reservoir for the exploration of potential therapeutic agents. In recent decades, a multitude of novel compounds have been unearthed from marine organisms, displaying intriguing pharmaceutical properties. This has led to the acknowledgment of marine organisms as promising candidates not only for the derivation of new bioactive substances for pharmaceutical advancement but also as a source of diverse biologically active compounds.

Several bioactive metabolites have been uncovered through screening initiatives, originating from cyanobacteria and marine algae. These chemical entities exhibit a broad spectrum of biological activities and possess varied chemical structures, garnering interest from biopharmaceutical enterprises. The medicinal worth of cyanobacteria dates back as early as 1500 BC, evident in the historical utilization of Nostoc for treating conditions such as gout and various forms of cancer. Over 40 distinct species of Nostocales have been identified as producers of around 120 distinct metabolites, demonstrating activities encompassing anti-HIV, antifungal, anticancer, antimalarial, and antimicrobial properties.4

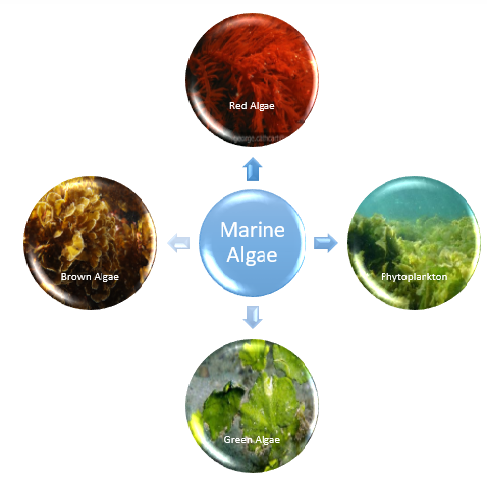

Figure 1

Representation of different types of macroalgae (Brown algae, red algae and green algae) and microalgae (Phytoplankto).

Marine algae stand out as prominent contributors to the extensive pool of crucial renewable resources within the marine ecosystem.5 Constituting biomass in this environment, they represent a class of rudimentary plants devoid of authentic root, stem, and leaf structures. These organisms exhibit a diverse array of chemically dynamic metabolites within their vicinity, which could potentially serve as a means to safeguard themselves from competing settling organisms. This classification positions them within the Thallophyta division of the plant kingdom. The taxonomy of marine algae encompasses four distinct groups, delineating their varying attributes and characteristics.6 Marine algae encompass a rich variety of distinct species, delineated primarily into two categorical divisions: microalgae and macroalgae. Microalgae, typified by phytoplankton, inhabit the aqueous column, whereas macroalgae, commonly referred to as seaweed, manifest as plant-like organisms, spanning in magnitude from several centimeters to numerous meters in extension. A case in point is the colossal kelp, which ascends from the seabed to create expansive submerged forests. Seaweeds have acclimatized to diverse habitats, thriving within diminutive intertidal rock pools proximal to the coastline, as well as colonizing waters several kilometers offshore, where the aqueous depths still permit adequate luminosity for photosynthetic activity. Algae are broadly categorized into three groups based on pigmentation of their algal body, or thallus. These divisions are chromatically represented by brown algae (phaeophytes), green algae (chlorophytes), and red algae (rhodophytes) (Fig.no. 1). Brown and red algae primarily inhabit marine domains, with certain species of red algae even inhabiting depths marked by exceptionally low light levels. In contrast, green algae inhabit both marine and freshwater ecosystems.7 In this review, the most recent findings in the study of biogenic synthesis of components derived from marine algae and seagrasses are compiled. The review offers crucial information on the developments in marine natural products, the types of inventions made to harness the purported medicinal properties of isolated marine compounds, the types of pharmaceutical products, as well as the key players and nations actively engaged in this field of study.

Extraction Strategies and Limitations

Numerous standard, non-conventional, or modern approaches have been developed and used to extract bioactive chemicals while taking into account the structural and compositional characteristics of target sources. Many traditional extraction techniques include preparatory fractionation of the parent material or crude extract, which makes it difficult to use them successfully on a large scale. While in other cases, several multi-step processing procedures during maceration, excessive water, energy, and chemical use can raise serious questions about the final product's quality and quantity. Longer extraction times, pure solvents, the consumption and evaporation of extra solvent, shortened extraction yields, heat degradation of thermolabile compounds, etc. are additional key drawbacks of classic extraction techniques.8 To address various limitations inherent in current methodologies, several promising and cutting-edge contemporary extraction methodologies, including techniques such as Enhanced Aqueous Extraction (EAE), Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE), and Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE), among others, have been documented in existing literature. Furthermore, the aforementioned advanced extraction approaches are also classified as environmentally sustainable due to their adherence to principles outlined by the green agenda.9, 10 In contrast to conventional methodologies, state-of-the-art contemporary extraction strategies offer substantial advantages, including environmentally friendly processing conditions, minimal or absent utilization of hazardous substances, safer solvent auxiliaries, efficient utilization of water and energy, reduced byproduct formation, employment of renewable raw materials, favorable cost-efficiency ratio, simplified sample preparation, optimal efficacy, prevention of degradation, and safeguarding against undesired chemical transformations.

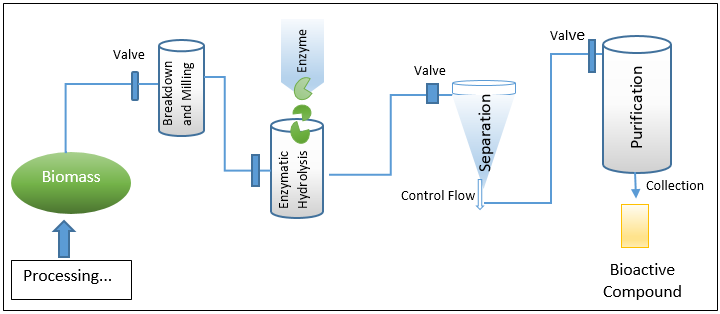

EAE – (Enzyme-assisted extraction processing and workflow)

Instead of being a genuine extraction process, this method is typically regarded as a pre-treatment strategy. The EAE-based processing and extraction environment's whole workflow is depicted in Fig. 2. EAE is frequently used to liberate inner bound molecules that are difficult to reach using a standard solvent extraction technique. Bioactive substances can occasionally be internally coupled via hydrogen or hydrophobic bonding, depending on the source and makeup of the material. Such materials are therefore put through EAE, which also improves the overall extraction yield. The release of highly valuable biologically active molecules and functional entities, as well as associated secondary metabolites, is efficiently facilitated by the mass transfer phenomena that is also induced by EAE. 11 From a workflow or action mechanism standpoint, adding extra amounts of certain enzymes like pectinases, oxidoreductases, cellulases, etc. helps break down the cell wall and hydrolyze polysaccharides and lipid compounds. 12 In the end, EAE also cause the recovery of intracellular highly valuable biologically active chemicals and associated functional entities, which are difficult to extract using traditional techniques. EAE offers notable advantages over conventional tools in practise, including I increased selectivity, (ii) induced efficacy, (iii) ease in extraction, (iv) safer and friendlier working conditions, (v) minimal energy requirements and usage, (vi) no or less use of harsh substances, (vii) higher end yield, (viii) no involvement of wasteful protection or deprotection stages, (ix) ease in isolation and product recovery, and (x) process recyclability.13, 14

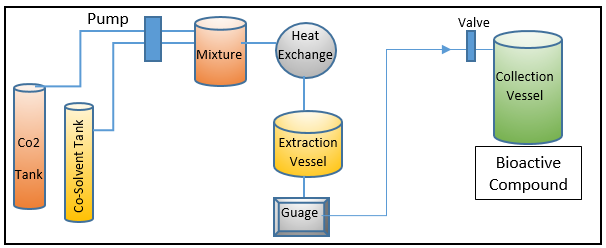

SFE – (Supercritical fluid extraction processing and workflow)

SFE is now widely used to extract high-value biologically active chemicals and functional entities, such as pigments and fatty acids. It has distinguished itself in recent years as a green method.15 SFE has many benefits over other extraction techniques used in practise, including excellent extraction selectivity, rapid processing, and minimal product degradability, 16, 17, 18 all without the use of non-food grade solvents. 18 In addition to the benefits already mentioned, SFE uses far less solvent than other extraction methods. 19 SFE uses supercritical fluids, as implied by its name, such as carbon dioxide (CO2), in its workflow or as an extraction mechanism to extract bioactive components from the source material. 20, 21 Due to its critical temperature, which is (31 °C), which is near to room temperature, CO2 is regarded as a suitable supercritical fluid in SFE. Additionally, it provides a low critical pressure of 74 bars with the option to function at moderate pressures, which typically vary from 100 to 450 bar.21 Figure 3 displays the whole workflow of the SFE-based processing and extraction environment. The solubility of the target bioactive biomolecules in the SFE is strongly influenced by supercritical fluidic dynamics. Among other influencing factors, the sample size and concentration both expressly contribute to the greater extraction yield and strengthen the cost-effectiveness of the overall extraction process.

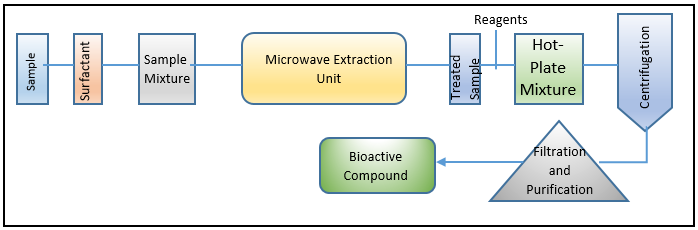

MAE – (Microwave-assisted extraction processing and workflow)

On the active exploitation of MAE in various industrial processes, a wealth of knowledge is accessible. Most frequently, MAE has been used to extract various industrially significant, high-value bioactive chemicals from a variety of materials, including phytonutrients, polyphenolic molecules, and components with medicinal activity.22, 23, 24 The MAE-based processing and extraction environment's whole workflow is depicted in Figure 4 Although the marine biome is a rich supply of high-value biologically active chemicals and functional entities, few extraction efforts have been conducted in light of marine sources. MAE has so far been utilised to extract highly valuable physiologically active molecules/functional entities from seaweeds and other algal sources using alkaline galactans, carrageenans, and agar.25, 26 From the workflow or action mechanism perspectives, the source material is exposed for a brief length of time in a confined area to microwave radiations, which are non-ionizing electromagnetic waves at N2000 MHz. Solvents are heated by the microwaves, which cause polar molecules to move and dipoles to rotate. In order to prevent sample boiling and/or heat deterioration, the irradiation is repeatedly performed with unbroken cooling phases for the best efficient extraction. The transfer of target bioactive compounds from the source matrix to the heated solvent is facilitated by such distinctive motion movements.27 The source material is first homogenised with the solvent to begin the extraction process. The most often used MAE solvents, which have varying polarity indices, include acetone, acetonitrile, ethanol, methanol, and dichloromethane. The microwave theory states that the electromagnetic waves are surrounded by two oscillating perpendicular fields, namely the magnetic and electric fields. The first, the electric field, is what causes sample heating.28 While the two phenomena (i) dipole rotation and (ii) ionic conduction determine the heating principle.28, 29, 30, 31

Medicinal and pharmacological properties

Seaweeds have been consumed in large quantities as food from the beginning of time since they are the primary source of vitamins and minerals.32 The extracts and its derivatives work well as dietary supplements.33 The antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal, antiallergic, anticoagulant, anticancer, antifouling, and antioxidant actions have also been used in addition to nutritional support against many biological illnesses.34 Sargassum wightii, a marine brown alga, has been reported by Yuvaraj 35 as having anti-tumor, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antibacterial properties. antioxidant processes Seaweeds contain strong anti-inflammatory and antioxidant characteristics that are essential in the fight against a number of illnesses, including cancer, atherosclerosis, chronic inflammation, and cardiovascular disease as well as the ageing process.35, 36 Additionally, it slows the development of cancer cells. 36 To prevent heart disease and stroke Utilizing seaweed can aid in lowering plasma cholesterol, which may lower the chance of developing cardiovascular disease.37 Antifungal and antibacterial properties Gracilaria corticata's crude methanol extracts are effective against both microbial and fungal growth. Methanol demonstrated the highest antibacterial activity against various pathogenic bacteria, including Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus epidermis, Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus cereus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Enterobacter aerogenes, among other solvent extracts like acetone, chloroform, and hexane-ethyl acetate.38 Another excellent source of an antibacterial agent is found in the Gracilaria corticata, Sargassum wightii, and Turbinaria ornate.39 As with methanol extracts against Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus, and Proteus species, ethanol extract demonstrated the highest antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus species.40 anti-inflammatory quality When tested against mouse ear edoema and erythema, methanol extracts of the seaweeds Undaria pinnatifida and Ulva linza shown greater anti-inflammatory efficacy. Seaweeds Undaria pinnatifida and Ulva linza effectively reduce edoema. These two seaweeds also had the greatest erythema suppression.41

Seaweeds as cancer preventatives The most significant sources of novel human medicinal chemicals are found in seaweeds. Experimental evidence suggests that several seaweed extracts can either weaken or completely eradicate cancer. Seaweed consumption has also been linked to the aetiology of breast cancer as a potential preventive factor.42 Both colorectal and breast cancer have been demonstrated to be resistant to the brown alga Fucus spp.43 Different seaweeds have been shown to have an anticancer effect on human colon and breast malignancies, according to research by Ghislain et al.43, 44, 45 Chinese medicine employed Laminaria sp. to cure cancer in the past, and old ayurvedic scriptures also mention it. Chinese medicine employed Laminaria sp. to cure cancer in the past, and old ayurvedic scriptures also mention it.45 Incorporating seaweed into your diet can help lower your risk of developing breast cancer and other cancers. a number of mechanisms via which the growth rate of cancer may be slowed. It entails lowering plasma cholesterol, binding biliary hormones, inhibiting cell adhesion, inducing apoptosis, binding harmful substances, and supplementing the diet with crucial trace elements. Diabetic prevention When used to treat diabetic rats, an aqueous extract of Ulva fasciata shown a good and notable change when compared to other conventional medication. Abirami (2013) 45 conducted a 28-day oral therapy experiment on diseased rats. During pretreatment with Ulva fasciata aqueous, he observed a considerable reduction in blood glucose and glycosylated haemoglobin levels. Abirami (2013)45 conducted a 28-day oral therapy experiment on diseased rats. During pretreatment with Ulva fasciata aqueous, he observed a considerable reduction in blood glucose and glycosylated haemoglobin levels.

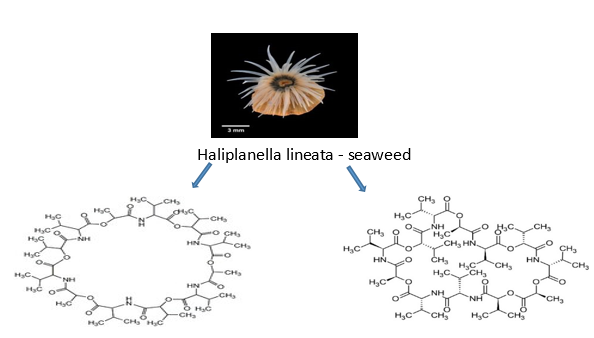

Anti-Cancer Activity

Streptomyces fulvissimus (ZZ40) is a species of bacteria that was isolated from the marine longitudinal seaweed Haliplanella lineata and was found in Wuhan Center, China. It produces streptomyces fulvissimus acid and streptomyces fulvissimus ketone chemicals. The Zhejiang University asserts that the substances are effective anti-tumor agents for the treatment of glioma, the most prevalent brain tumour with a high fatality rate.46 As studied utilising human glioma U87MG cells, tricarboxylic acid cycle enzyme aconitase 2 (ACO2), and oxidative phosphorylase cytochrome C, these drugs exhibit considerable anti-glioma action by specifically targeting numerous critical enzymes of glioma glycolysis (CytoC).

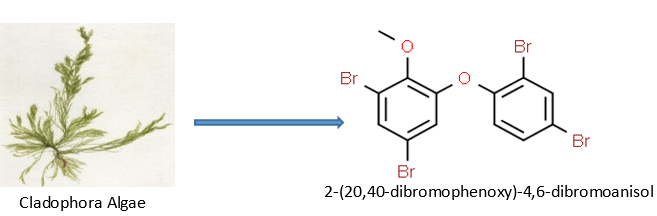

Antimicrobial Activity

Cladophora algae have been shown by M. Kuniyoshi to exhibit antibacterial activity against specific microbes in yet another investigation. To obtain 2-(20,40-dibromophenoxy)-4,6-dibromoanisol47, the green algal extract of Cladophora fascicularis was separated using several chromatographic procedures. Additionally, it actively impeded the development of S. aureus, Bacillus subtilis, and E. coli.47

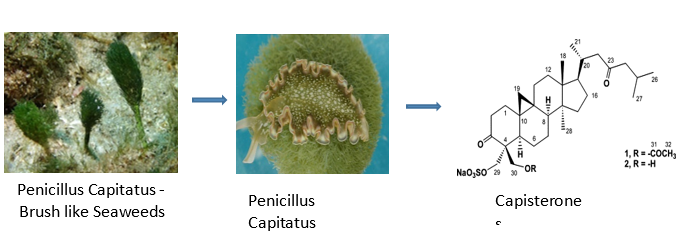

Antifungal activity

Capisterones, which are sulfate esters of triterpenes found within the green algae Penicillus capitatus, exhibit potent antifungal activity against the algal pathogen Lindra thallasiae.48 Crude extracts from certain red algal species were examined for the presence of antibiotic activity against few pathogenic fungi.49 The eminent fungicidal activity was found in marine macroalgae to recover patients from chronic asthmatic states. In particular, L. paniculata was studied to have excellent antifungal activity and so it is recommended as a promising candidate to attain a novel antifungal agent.50

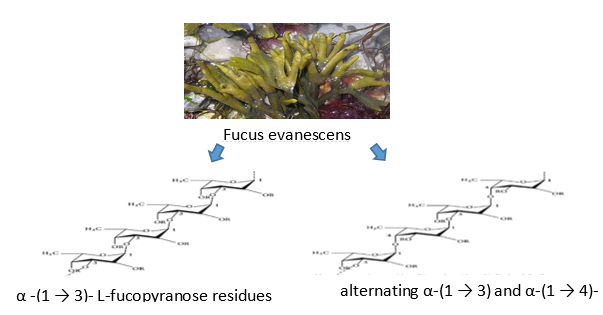

Antiviral activity- Mechanism of sulfated polysaccharide

Sulfated polysaccharides from marine sources have unusual structures that have antiviral effects. By directly inactivating virions before to infection or by preventing its proliferation inside the host cell, it prevents several stages of the viral life cycle. As a result, polysaccharide-rich seaweeds play a significant role in the discovery and creation of antiviral medications. The main phases of a virus's life cycle, which vary depending on the species, include attachment, penetration, uncoating, biosynthesis, viral assembly, and release.51 Alternative units of α -(1 3)-linked and α -(1 4)-linked L-fucopyranose are present in the fucoidan from the fungi Fucus evanescens and Ascophyllum nodosum. A heterogeneous sulfated polysaccharide called fucoidan makes up 25–30% of the dry algal weight. It has a backbone made of L-fucopyranose residues that are α -(1-3) or alternate α -(1-3) and α -(1-4) connected L-fucopyranosyls.52, 53

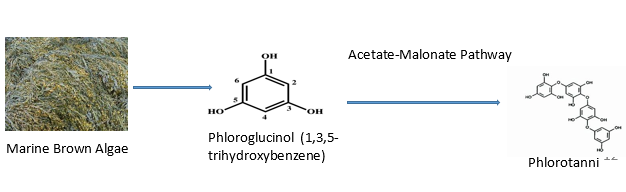

Antioxidant activity

In the later phases of cancer development, antioxidants are crucial. There is mounting evidence that oxidative mechanisms encourage the development of cancer. In recent years, numerous algae species have also been found to be able to stop the growth of cancer cells by scavenging free radicals and active oxygen and preventing oxidative damage.54 Antioxidants are likely the molecules in algae that are most important and have garnered the most attention. In the fight against numerous illnesses (such as cancer, chronic inflammation, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular disorders), antioxidants are regarded as important molecules.55 Phlorotannins, a type of polyphenol found in marine brown algae, are recognised as possible antioxidants. Phloroglucinol (1,3,5-trihydroxybenzene) monomer units are polymerized to form phlorotannins, which are produced by marine algae using the acetate-malonate pathway. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that sulphated polysaccharides extracted from marine algae have both in vitro and in vivo radical scavenging properties. However, biochemical scientists have several techniques to extract bio-active compounds from algal biomass.56

Chemical profiling of crude extract

Since extracts are combined with contaminants and it is crucial to separate them, each analytical procedure had one or more components to analyse. For the examination of algal extractives, gas chromatography (GC) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) are both widely utilised techniques.57 The most accurate and popular method for separating a variety of substances is HPLC. Pharmaceutical grade analysis has been carried out using (LC-MS) and (GC-MS) technologies.58 One of the often used analytical techniques is reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC), although this technology is unable to distinguish between highly polar and less polar substances, according to Herrero et al.59 Fast SFE extracts characterisation utilising capillary electrophoresis with diode array detection (CE-DAD) is thought to be a good alternative to RP-HPLC since it exhibits faster application times, more efficiency, and greater selectivity than HPLC.60, 61 Many researches used 1D, 2D NMR, MS/MS, HPLC, and chiral GC-MS analyses to conduct complete structure characterization of bioactive natural compounds.62, 63, 64, 65 Algal fatty acids were evaluated by LC-MS and GC-FID to determine their methyl or ethyl esters between 2005 and 2010, as described by Bernal et al.66 in their explanation of analysis methodology.66 Gas chromatography (GC) in conjunction with several detection methods, including ECD, FID, and MS as well as HPLC, when coupled to one of the following detection systems, is used to identify lipids: We advised PDA, UV, MS, and MS/MS. Other recommended analysis methods were mass spectrometry (MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). Terpenes can be analysed using GC-MS, HPLC-UV-MS, or NMR, however NMR is preferable for structure investigation. Bernal et al.66 have enumerated various analytical methodologies employed in the identification and quantification of carotenoids, including High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) equipped with Diode Array Detection (DAD) or Ultraviolet (UV) detectors. The fusion of Liquid Chromatography with Photodiode Array (PDA) and Mass Spectrometry (MS) detectors has demonstrated heightened sensitivity in the detection of both carotenoids and carotenoid esters.67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72 In the context of analyzing carotenoids with antioxidant and anti-cancer properties, such as β-carotene, the utilization of HPLC with UV/Vis or DAD detection has been recommended.

Case I

L. MacKinnon et al. conducted an investigation titled "Analysis of Betaines from Marine Algae Using LC-MS-MS." This study focused on the analysis of betaines, which belong to a category of quaternary ammonium compounds present in marine algae. These compounds have the capacity to function as osmolytes and have the potential to influence gene expression. Consequently, they hold the promise of enhancing plant tolerance to various stressors such as extreme temperatures, drought, and salinity when applied to agricultural crops. In human biology, glycine betaine serves as a methyl donor and has exhibited protective effects on internal organs, enhancement of vascular risk factors, and improvement of athletic performance.

Using thin layer chromatography and NMR methods, more than 13 betaine analogues have been found in the seaweeds Chlorophyta (green), Heterokontophyta (brown), and Rhodophyta (red). 73 Thin layer chromatography, 74 thin layer electrophoresis, 75 and non-specific precipitation reagents were early analytical techniques used to quantify betaines in plants, seaweeds, or commercial seaweed extracts. 76, 77 Since the late 1970s, there has been continuing development of an HPLC-based method for betaine analysis. 78 Due to their weak chromophoric moiety, betaines do not glow noticeably and are only detectable at low UV wavelengths (190–220 nm). 79 Because betaines aren't reactive to several reagents, attempts to raise the detection limits of betaines using those reagents haven't produced adequate results. 80 The limitation of proton magnetic resonance (1H NMR) as a technique for betaine analysis for seaweed extracts and plant material is that it is unable to measure the concentrations of betaines that are present as small components. 81

The present study outlines a Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS-MS) technique for the quantification of betaines within seaweed specimens and commercially available seaweed extract products. This method involves a swift sample preparation and purification protocol. Leveraging the heightened sensitivity and specificity of LC-MS-MS, this approach proves to be well-suited for the systematic evaluation of glycine betaine, γ-aminobutyric acid betaine, δ-amino-valeric acid betaine, and laminine. 82, 83

Case II

The chemical components residing within Streptomyces sp. strain Al-Dhabi-97, which was isolated from a marine locale, were scrutinized by Naif Abdullah Al-Dhabi et al. 84 The constituents were subjected to analysis using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) in conjunction with Mass Spectrometry, a technique chosen for the purpose of characterizing the individual elements within the ethyl acetate extract derived from the Al-Dhabi-97 isolate. The instrumental setup involved coupling the GC-MS apparatus with a capillary column, where the samples were separated and eluted through the application of low-pressure helium gas at a flow rate of 1000 mL/min.85 The temperature of the column was programmed to range from 40°C to 280°C, while the temperature at which the samples were injected stood at 280°C.

Conclusion

The nomenclature of marine-derived materials is continually evolving due to the rapid discovery of new compounds exhibiting novel functionalities. From a prospective standpoint, exploring novel sources within diverse marine biomes presents an avenue for investigating analogs with enhanced activity, selectivity, and reduced toxicity. Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) holds significance due to its intermediate diffusivity and viscosity values, positioned between gases and liquids. Supercritical fluid extraction proves advantageous by enabling faster and more efficient extraction, owing to its thorough penetration into biomass structures. Since its groundbreaking discovery, SFE has emerged as a highly efficient extraction method across multiple domains.

Ongoing advancements in nanotechnology offer potential to facilitate the separation and identification of highly functional entities. These practices have the potential to open new avenues for research and development in the near future. In this context, the investigation of bioactive marine compounds is anticipated to persist as a focal point across diverse sectors. Moreover, this pursuit stands to revolutionize and broaden the utilization and applicability of these novel natural sources. In summation, the marine domain is poised to remain a subject of intensive research endeavors spanning various contemporary sectors.

The progression of sophisticated analytical techniques is imperative within algae research to effectively characterize, identify, and quantify natural constituents within studied species. Amid the array of analytical technologies, including High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), Gas Chromatography (GC), Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC), Mass Spectrometry (MS), and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), certain methods employ combined approaches like HPLC-MS, GC-MS, and HPLC with Diode Array Detection (HPLC DAD) for comprehensive and precise identification and quantification of target compounds.